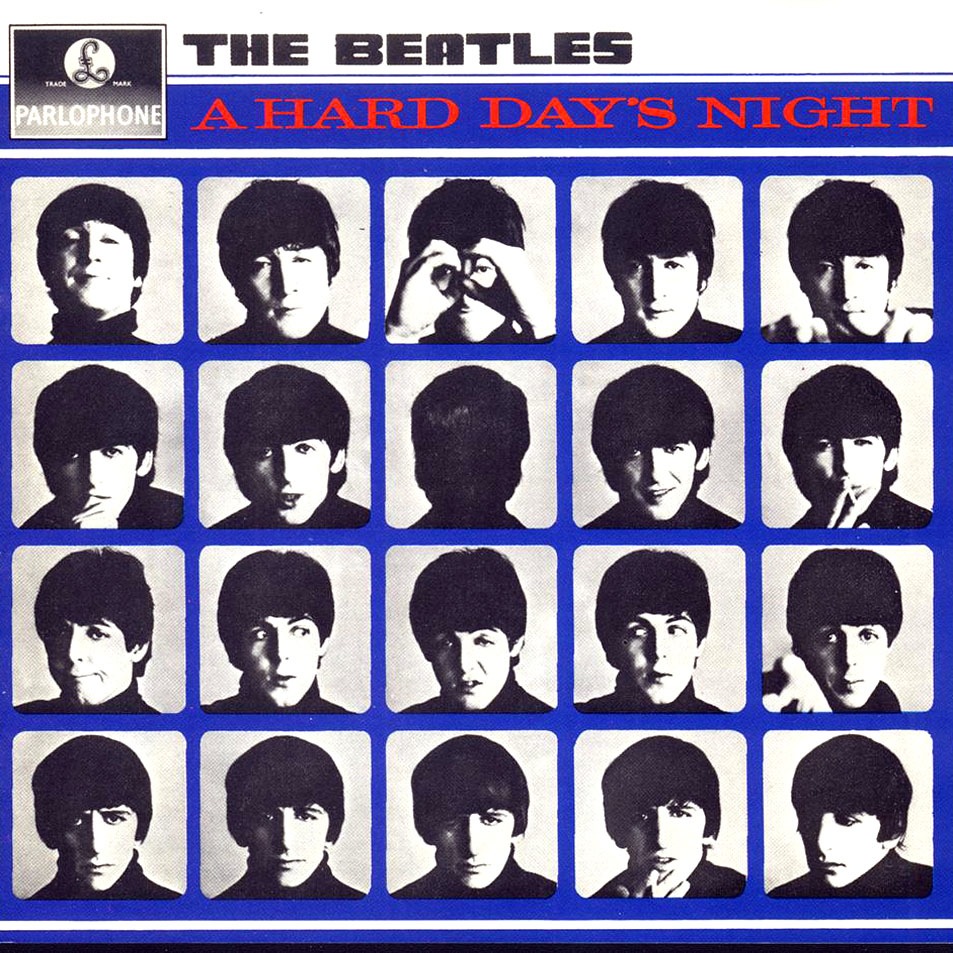

1964 a Beatles világméretű robbanásának éve, letarolnak minden slágerlistát, beveszik Amerikát, és a pop-zene után a filmvásznon is hódítanak. A sors különös fintora, hogy a „nagyonangol, nagyonliverpudli” fiúkat egy Pennsylvaniából áttelepült amerikai rendező irányítja, aki igazán a szigetországban vált híressé. A Fab Four és Richard Lester zseniális találkozása az A Hard Day’s Night, vagy magyarul az Egy nehéz nap éjszakája, amelyet annak idején csak 4 év késéssel mutattak be hazánkban – akkor, amikor a Beatles már zeneileg és emberileg egyaránt túl volt akkori önmagától, de sem a mozi, sem a zene nem porosodik azóta sem.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cn0_qWYMROY

Egy amerikai kritikus „a wurlitzer Aranypolgára” címmel tüntette ki Lester és a Beatles filmjét. Persze minden összehasonlítás sántít, de az kétségtelen, hogy ahogy Orson Welles filmje mérföldkő a sajtó ábrázolásában, úgy az Egy nehéz nap éjszakája is merőben új stílust hozott a „zenés könnyűzenei filmek” műfajában. Voltak már korábban is olyan filmek aktuális sztárok főszereplésével Elvis Presley-től Cliff Richardon át Bobby Solóig, amelyeknek egyetlen céljuk volt: a futó slágerek népszerűsítése, a dalokat pedig beleágyazták többnyire valami szirupos, természetesen happy enddel végződő történetbe. A Beatles ezzel szemben önmagáról készített „mockumentary”-t, azaz ironikus dokumentumfilmet, amelyben nemcsak a show-bizniszt, a sztárkultuszt, a bulvármédiát fricskázzák meg, hanem saját magukat is, megtetézve egy rémségesen csúnya, született bajkeverő nagypapával. (Wilfrid Brambell). Bár volt a filmnek forgatókönyve, Alun Owen munkája, John, Paul, George és Ringo ezt fölöttébb szabadon kezelték, a poénok többségét ők találták ki menet közben, beleszőve az angol nonszensz humor elemeit, évekkel megelőzve a Monty Pythont. (Mellesleg két hónappal a filmbemutató előtt jelent meg John Lennon első kötete, a lefordíthatatlan című In His Own Write, abszurdjaival, nyelvfacsaró verseivel és jeleneteivel.) Nem kellett szerepet játszaniuk, önmaguk lehettek – paradox módon ellentétben a hajszás turnék világával, az őrjöngő rajongók sikításától számukra is élvezhetetlen koncertek sorozatával.

Maga a lemez csak félig „sound-track”: az LP első oldala tartalmazza a filmben elhangzott új dalokat, míg a második oldal a „maradék” – soha rosszabb resztlit, sőt, egyes ítészek szerint ez utóbbi igényesebb. Ízléseken nem érdemes vitatkozni, az viszont tény, hogy a filmzene-oldalon minimum négy abszolút klasszikus hallható: a címadó, rohanva csengő-bongó dal, hatalmas, nyitány-szerű, 12 húros gitárleütésével, a gyermekien egyszerű, játékos-szájharmonikás I Should Have Known Better, ami a filmben kétszer is elhangzik – egyszer a vonaton, egyszer a koncerten (ez utóbbiból egy részlet bekerült Kovács András 1968-ban készült Extázis 7-től 10-ig című filmjébe is) - a Beatles-líra egyik legszebb darabja, a latinos-akusztikus And I Love Her George Harrison kifinomult gitárszólójával és Ringo Starr bongóival, és végül Can’t Buy Me Love erőszakos rhythm-and-blues-a. Ez utóbbihoz fűződik a film labda nélküli rögbi-jelenete, amely állítólag Michelangelo Antonionit is megihlette a Nagyítás teniszpantomim-zárójelenetéhez. És akkor még ott van az If I Fell különleges spirális szerkezetű dallama, a sokszor megcsodált Beatles-vokállal, amely végképp megcáfolja a „Beatlest játszani bárki tud” kezdetű nagyképű kijelentést.

A második oldal is bővelkedik finomságokban: Paul McCartney évtizedekkel később is büszke volt a kissé baljós hangulatú Things We Said Today akkord- és ritmusváltásaira. Lennon az I’ll Cry Insteaddel mintegy megelőlegezi témájában és hangulatában a Help!-et, csak még kevesebb benne a kétségbeesés. A You Can’t Do That-tel Paul Can’t Buy Me Love-jára válaszol a nem kevésbé dögös R&B-zal, míg az I’ll Be Back melankóliája az And Love Her ellenpárja. Ekkoriban kezdett John és Paul külön dolgozni és ez az egészséges rivalizálás a konkrét dalokban is tetten érhető.

Lester és a Beatles közös története még folytatódott: a Help! James Bond-paródiájából (1965) sajnos hiányzik az a spontainetás, ami az első filmet jellemezte, de ma is nézhető, a zene pedig újabb árnyalatokkal gazdagította az együttes immár ezer színű palettáját. 1967-ben a rendező Lennont hívta meg a Hogyan nyertem meg a háborút? című gyilkos szatírájához, amely nemcsak John fekete humorával, hanem hamarosan kibontakozó békeharcos tevékenységével is összhangban volt.

Richard Lestert (1932. január 19) később is a szellemes, fordulatos, remek tempóval vágott filmek mestereként ismerték. 1965-ben A csábítás trükkjével (The Knack ...and How to Get I) tCannes-ban Aranypálmát nyert, nagy sikert aratott a Pénzt vagy életet! terrorista történetével (1974), a Superman II. és III. részével, de alighanem legemlékezetesebb a Három testőr-trilógiája, amely sok tekintetben rímelt az Egy nehéz nap éjszakájára: mindkét film a barátságról, az együvé tartozásról, a kalandvágyról, a féktelen életszeretetről (is) szól, de ahogy a Beatles-filmben a rajongással párhuzamosan kifigurázza a modern szórakoztató ipart, a Dumas hősei iránti tisztelet mellett idézőjelbe teszi az egész mítoszt, a testőr-romantikát. Lehet, hogy csupán a véletlen műve, hogy az Egy nehéz nap éjszakáját Olaszországban Tutti per uno (Mindenki egyért) címen vetítették?

Track list:

A oldal:

1. A Hard Day's Night

2. I Should Have Known Better"

3. If I Fell

4. I'm Happy Just to Dance with You

5. And I Love Her

6. Tell Me Why

7. Can't Buy Me Love

B-oldal:

8. Any Time at All

9. I'll Cry Instead

10. Things We Said Today

11 When I Get Home

12. You Can't Do That

13. I'll Be Back

Következik: The Yardbirds: Five Live Yardbirds (1964)